1-07 Bonds

Unlike stocks, which are equity instruments, bonds are debt instruments. When bonds are first issued by the company, the investor/lender typically gives the company $1,000 and the company promises to pay the investor/lender a certain interest rate every year (called the Coupon Rate), AND, repay the $1,000 loan when the bond matures (called the Maturity Date). For example, GE could issue a 30 year bond with a 5% coupon. The investor/lender gives GE $1,000 and every year the lender receives $50 from GE, and at the end of 30 years the investor/lender gets his $1,000 back. Bonds differ from stocks in that they have a stated earnings rate and will provide a regular cash flow, in the form of the coupon payments to the bondholders. This cash flow contributes to the value and price of the bond and affects the true yield (earnings rate) bondholders receive. There are no such promises associated with common stock ownership.

After a bond has been issued directly by the company, the bond then trades on the exchanges. As supply and demand forces start to take effect the price of the bond changes from its initial $1,000 face value. On the date the GE bond was issued, a 5% return was acceptable given the risk of GE. But if interest rates go up and that 5% return becomes unacceptable, the price of the GE bond will drop below $1,000 so that the effective yield will be higher than the 5% Coupon Rate. Conversely, if interest rates in general go down, then that 5% GE Coupon Rate starts looking attractive and investors will bid the price of the bond back above $1,000. When a bond trades above its face value it is said to be trading at a premium; when a bond trades below its face value it is said to be trading at a discount.

Here is an example with a bit more of a breakdown:

If you buy a bond at $1000 that pays a 5% coupon, then every year you will get $50 back in interest and when the bond matures you get the $1000 par value. So in this case, your yield is 5%.

If you paid $900 for the bond, you would still get $50 in interest every year plus the $1000 par value when the bond matures. So the $50 return on the $900 cost is 5.55% return per year and the $1000 back on the $900 is another good return so the overall yield will be OVER 5.55%.

If you paid $1100 for the bond, you would still get $50 in interest every year plus the $1000 par value when the bond matures. So the $50 return on the 1100 cost is 4.54% return per year and the $1000 back on the $1100 initial investment is a negative return so the overall yield will be LOWER than 4.54%.

Understanding the difference between your coupon payments and the true yield of a bond is critical if you ever trade bonds.

There are three common types of bonds available for general sale. They offer different levels of security and projected earnings:

Treasuries:

U.S. Treasuries carry the full faith and credit of the U.S. Federal government. Therefore, purchasing Treasuries eliminates much of the risk associated with most investments. As you can imagine, in return for this minimized risk, your earnings rate will also be less than with most of the more “exotic” investment choices.

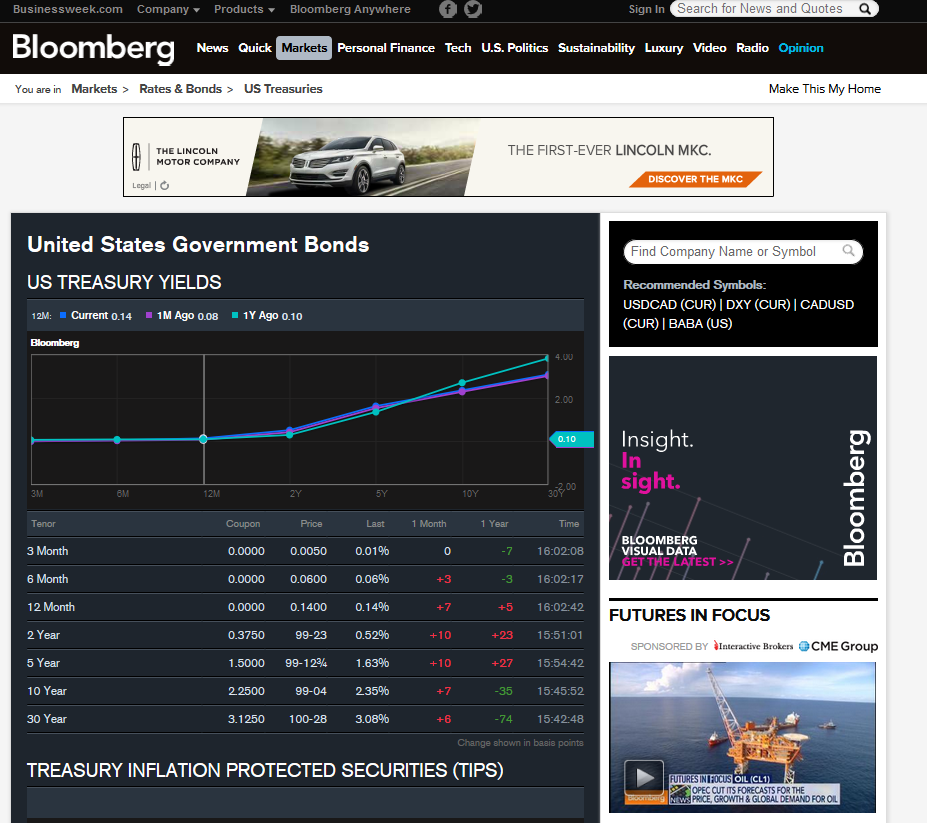

Treasuries, particularly the 3-month Treasury bill, are sometimes quoted as the “risk-free rate of return,” the minimum rate of return an informed investor will accept for enjoying the minimum risk. In the real world there is no true risk-free investment, although Treasuries do come close. Below is a snapshot of the Government bond page from Bloomberg.com:

You should also understand the meaning of a “yield curve“. Displayed graphically above, a yield curve is the relationship between the interest rate offered and the time to maturity of an investment. While all investments have a yield curve, many traders and economists closely follow the yield curve of Treasuries of different maturities to help make other financial decisions and projections.

Corporate Bonds:

These bonds can be quite secure or sometimes risky. Their inherent value is greatly determined by the credit worthiness of the corporation offering the bonds. Be aware that corporate stability can change over time. For example, until 2009, most bonds offered by U.S. automakers implied good levels of security. However, the bankruptcies of GM and Chrysler, combined with serious financial problems at Ford (F), generated much higher risk factors for their corporate bonds. Typically, however, corporate bonds are more secure than corporate stocks.

Municipal Bonds:

States, cities, or other local governments often issue bonds to raise money to fund services or infrastructure projects (road and bridge repair, sewers, purchasing open land, etc.). The primary advantages to investors are security and tax benefits. For example, most municipal bonds offer interest earnings that are exempt from federal taxes. In addition, if you are a resident of the state in which you own one or more municipal bonds issued by local governments, your earnings may also be exempt from state or local taxes. Never assume a high security factor, however. Some local governments may be in dire financial condition and your risk factor may outweigh any tax benefits you enjoy.

Bonds are not nearly as liquid as stocks and ETFs, and therefore there is not nearly as much information publicly and freely available. If you are going to buy bonds, always buy them from a reputable source and always check your prices to make sure you are getting a fair price. Also, you must remember that when you buy a bond your return is called the Yield to Maturity and NOT the Coupon Rate. If you buy a bond below $1,000 you will yield MORE THAN the Coupon Rate; and if you buy a bond above $1,000 you will yield LESS THAN the Coupon rate.